Free Will & Determinism

Philosophical Reflections VIII

Do human beings have free will, or are our actions pre-determined? This is an ancient question.

Determinism comes in many forms: theistic (predestination by an omnipotent god), fatalistic (“what will be, will be”), mechanistic (the inexorable paths of atoms), and behaviourist (determination by psychological conditioning).

To have free will is to be morally responsible: if you have the power of choice then you can justly be held accountable for those choices. If your choices are outside your control, then you cannot be held accountable (according to some religious beliefs, God determines your choices then holds you responsible anyway: the meanest trick you could play on a conscious being). There can be no justification for praise or blame, reward or punishment, under determinism: except as a pragmatic tool of social control (by who?).

Basics

Free will is the power to choose between alternative courses of action. Clearly, it has meaning only in the context of the nature of man and the nature of reality. Your will is not less free because you cannot “choose” to walk through walls or float unaided to the stars. Free will is the power, when confronted by more than one physically possible course of action, to choose freely which to do, without coercion by others or predetermination by external events.

It is quite plain that human beings have wills. Volition is fundamental to consciousness, as our conscious mind is what directs our actions. The question is, however, is that will free ? Or are all our decisions, our choices and our gambles, just the results of unknowable forces, our “will” a shadow and a sham? Are we just onlookers, slaves to our fate: or masters of our destiny?

Two Invalid Approaches

Because mechanistic determinism arose from the idea that atomic motions were infinitely predictable, the supposed inherent randomness of quantum mechanics has been put forward in support of free will. Unfortunately, having our wills the result of random processes rather than predictable ones does not really do us any good! Either way, our choices are outside our control.

From the other side, it has been argued that if the mind is simply a function of the brain then our wills have physical causes, therefore we are not free. This is a variant of an ancient dilemma that either our wills have causes and so are determined, or they are causeless and hence chaotic. Clearly this does not actually depend on the answer to the mind/brain question (which can be decided only by science, not philosophy). In fact, as I will show, our wills do have causes but they are nevertheless free.

Philosophic Axioms

Some things are so fundamental that everyone must assume them, even to dispute them. These are “philosophic axioms”. For example, to argue against the inherent validity of reason, or the concept of “truth”, or that words can communicate meaning, one must assume the contrary: and not only assume it, but use and rely on it.

Fortunately, such axioms are not only necessary, but self-testing. As we must assume them in all we do and think, we would soon find out if they were wrong.

If we could disprove a philosophic axiom, we would be left in an untenable position. For example, if we could use reason to disprove reason, once we reached that conclusion there would be nothing more we could say.

Yet, those who dispute philosophic axioms usually proceed to advance complex arguments at great length. Clearly it is the minds of others, not their own, which they wish to disable. Any such argument which if applied to itself, invalidates itself or renders itself meaningless, vanishes up its own metaphysics. The only valid response to a successful disproof of a philosophic axiom is

Free Will is Axiomatic

All philosophy presupposes free will. If our wills are not free, then arguments are pointless and ethics are futile.

If determinism is true, why bother arguing for it? Arguments to change an opponent’s mind only make sense if the opponent is free to change it. Of course, determinists have an out here: after all, they can’t help themselves! However, as with all attacks on philosophic axioms, it is a rare determinist who accepts the implication that he is just a driverless machine parroting futile sounds.

Nevertheless, any serious attack on an axiom requires an answer. If reality is such that our minds are impotent, then we need to know: and if it is not, then we need to be able to answer those who would make us impotent. If we assume our minds are free and, using them, can prove that they are not, then that’s that. Like disproving reason itself, this leaves us in limbo, incapable of action and incapable of escape. We might as well eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die: except we’d have no power to make that choice!

So the question is, can we prove determinism, or not?

Antecedents of Choice

No behaviour is without cause. The question is, how does this relate to volition? A useful approach is to examine the details of cause and effect, of what factors are responsible for actions in increasingly complex living things. When we discover what information we need in order to predict how something will behave, we can see to what extent it is free.

The Scum of the Earth

Protozoa, single-celled animals, have no consciousness or will. They react to their environment: their actions are determined by the motion of atoms and molecules.

However, unlike a grain of salt dissolving in water, the laws of chemistry are not enough to predict their behaviour. The responses of protozoa depend on macromolecules such as proteins, whose function depends on their three-dimensional shape (itself influenced by many factors), and on their mutual interactions. Although this ultimately derives from the fundamental laws of physics, the immediate causes of protozoan behaviour are the laws of biochemistry.

There is a much more important difference. These creatures have purpose . They seek food: they swim and hunt. Their biochemistry is not merely reactive: it gives them self-starting drives.

Life is active, not passive. This is a necessity of its nature. Life is the growth of order out of disorder, complexity in the face of chaos: it is anti-entropy. The only way this is possible by physical laws is by the directed expenditure of energy. This requires the seeking of sources of energy and the organisation to use them.

Thus, life is not merely determined by its environment: it actively changes that environment. A protozoan swims, changing the courses of atoms. It eats, excretes and respires. So its future depends on its own actions, and those of other life. It is still deterministic, but it is far from simple: and it is now a two-way street.

Animals

A complex animal such as a dog is removed even further from chemical determinism. Like a protozoan, a dog both responds to its environment and has active drives, but its behaviour as an organism is now primarily determined by its brain, not its biochemistry. Once again, although brain function depends on more fundamental laws, its own laws are the immediate causes.

A dog’s behaviour depends on its drives, its current physiological state, what it has learned, and its psychological conditioning. It learns what actions lead to punishment and what actions lead to reward (physical or social), and its future behaviour depends on this. Thus to predict what a dog will do, you need to know not only its physical needs and state, but its mental history. A yet higher order of decision-making, further removed from the atomic level, has to be accounted for.

To Be Human

Human beings are animals. Conditioning affects us too. However, with us there is a vital extra step: we are rational beings.

This means that when faced with choices, we can decide what to do based on reason. Taking what we know, what we value, and the present circumstances, we can use the laws of logic to determine what we should do. A rational being is not a collection of automatic responses: his or her responses are decided on the basis of facts and logic.

Thus to predict the actions of a man, the motions of atoms are not enough; biochemistry is not enough; his past conditioning is not enough: his reason must be taken into account. And here, determinism is derailed. Reason is absolute: a valid course of action is valid not because of conditioning or any other influence, but because of what reality is . Reason is not a whim, nor the accidental matter of the moment: its validity is founded in the nature of reality (the laws of logic reflect the fundamental laws of reality).

But does this lead to an infinite regression? Must we first decide to use reason, and if so, how? No, we don’t have to: that is founded directly in reality, in the reality of man. It is our nature to use reason . When we wake, we start thinking; we cannot function normally without using reason; the very human responses of noting an inconsistency, or being puzzled, are rooted in reason. We can decide, based on our values, that we won’t think; that we will evade reality; that we’re happy to carry dozens of contradictory beliefs with no attempt at integration: but those decisions are made by a being who has no choice but to make some decision, a being who has no choice but to think even in the act of deciding not to.

A determinist can say a protozoan is controlled by biochemistry, a dog by conditioning: but what can he say about a man? “Of course what you did was determined: you came to a conclusion as to the course of action most in accord with your values, and did it. You had no choice: it was the only logical thing to do.” But this is free will. If we can decide what is objectively our best course of action, what is in accord with achieving our values and desires, and do it: then what more needs to be said? How could we be more free?

Consider the chain of causation. The atomic arrangements that make up our brains are such that those brains (1) have active consciousness, which seeks to understand the world, maintain life and improve well-being; and (2) have the power of reason, allowing direct assessment of how to achieve those things. That is, by direct, deliberate reference to reality, bypassing the action of blind, unfathomable forces. Thus our actions have causes but are not determined: we act according to our nature, but our nature is to be free. That we are conscious means we are not mindless automata; that we have reason means our consciousness is not merely blown hither and yon by random forces of the world.

Compare an integrated, rational person with a mentally ill man who is ruled by wild emotions he cannot understand or control. Which is free? It is precisely when a normal person experiences a shadow of the latter that he is not completely free and knows it; it is precisely when he is being rational, when his emotions are in tune with his reason, that he feels and is the most free, for he is able to do what he judges is best.

How free we are is a matter of choice. Our values can be rational or irrational. We can accept the random conditioning of our environment, or apply our minds. At any stage, we can stop and think: “Are my values and goals really valid?” Even with a neurosis (conditioning gone badly wrong), we can by reason realise that there is a problem and seek professional help. Indeed, as our nature is to think, the choice between freedom and slavery is always there, though the more we choose the latter, the harder it is to change.

Thus the answer can be summed up in three words:

Reason is freedom.

*

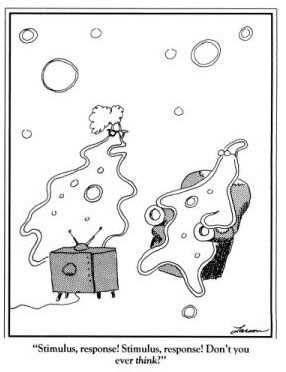

As usual, Gary Larson’s The Far Side gets it right.

© 1993, 1996 Robin Craig: first published in TableAus.